South African style has always been more than visual expression — it is a record of survival, resistance, and joy. From football terraces to township streets, from sound systems to dance floors, Black South African culture has long shaped how the country looks and moves. What has changed is not the creativity itself, but its market value.

As South African pop culture increasingly influences global fashion, music, and lifestyle trends, an urgent question emerges: who benefits when Black South African stories become desirable?

Kasi Flavour: South African Culture as a Living Archive

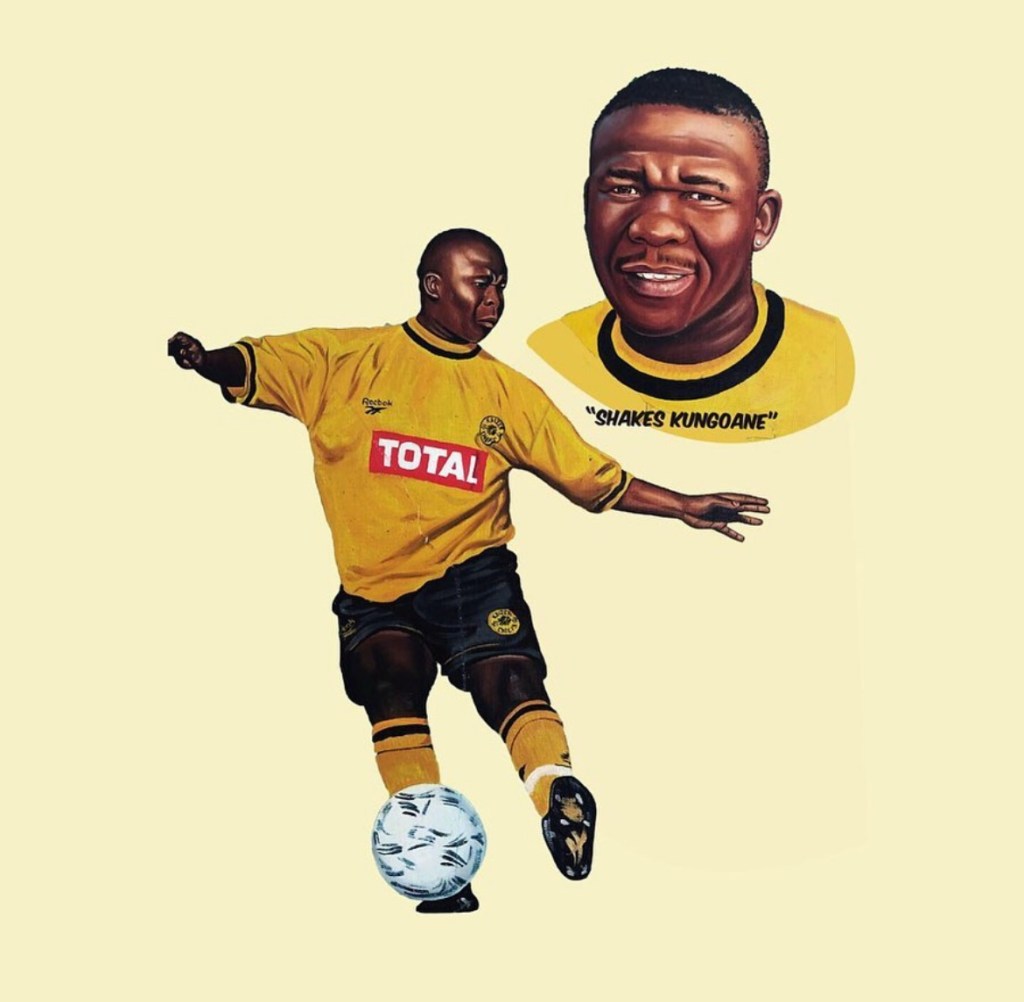

Kasi Flavour is deeply rooted in South Africa’s football history. The brand exists at the intersection of sport, township life, and memory — archiving and preserving a distinctly South African football culture inspired by kasi aesthetics and hood sensibilities that have defined the local game for generations.

This culture was never designed for export or external validation. It emerged from local rituals: match-day gatherings, community teams, worn jerseys passed down through families, and the unmistakable style that formed around South African football spaces. Kasi Flavour does not simply reference these worlds — it emerges from them.

In this way, the brand functions as a living archive. It connects South Africa’s past to its present, ensuring that the visual language of township football culture is documented, respected, and carried forward on its own terms.

Old School: When Resources Enter the Culture

Old School, by contrast, operates with significantly greater access to capital, infrastructure, and commercial networks. While it may now draw from similar South African visual codes and cultural references, it does so from a position of power.

With resources comes reach: the ability to scale faster, secure high-profile brand deals, and occupy spaces that smaller, culture-rooted brands often cannot. The business models may appear similar on the surface, but the outcomes are not.

What begins to emerge is a familiar pattern in South African fashion: the culture originates in Black township spaces, but the financial rewards concentrate elsewhere.

South African Pop Culture Is Shifting the World — But For Whom?

From music and dance to fashion and street style, South African pop culture is shaping global trends in real time. Amapiano, township aesthetics, football-inspired silhouettes, and local slang have become global reference points.

Yet while Black South African stories are being told, sampled, and celebrated, the people who initiate these cultural movements are often excluded from their economic upside. Those with greater resources — stronger funding, established networks, and institutional access — are better positioned to monetise what others have lived.

This is not simply about influence or inspiration. It is about extraction.

Visibility Without Ownership

The problem is not exposure — South African culture has never lacked visibility. The problem is ownership.

When brands closest to the culture struggle to access funding, partnerships, and long-term sustainability, while better-resourced entities benefit from the same cultural language, visibility becomes hollow. Celebration without equity reinforces old hierarchies, even when wrapped in new aesthetics.

Kasi Flavour carries the labour of preservation, authenticity, and cultural memory. Old School carries the benefits of scale, access, and commercial legitimacy. When these realities coexist without redistribution, the imbalance is structural — not accidental.

So, Who Benefits From South African Culture?

When South African aesthetics become marketable, profit tends to follow access, not origin. Black South African stories travel the world, but the economic rewards often stop short of the communities that created them.

If South African fashion and pop culture are truly shaping the future, then the people who live, build, and sustain these cultures must also be allowed to own them — financially, historically, and creatively.

Until cultural capital is matched with economic power for those who build from within, township culture will continue to be celebrated in imagery while remaining excluded from long-term wealth creation.

The question is not whether South African aesthetics deserve global platforms — they already do.

The question is whether the people who live the culture will be allowed to own its future.

Leave a comment