This year in South African fashion did not announce itself loudly or neatly. There was no single silhouette, colour, or moment that defined the months gone by. Instead, what unfolded was quieter and more layered — a series of shifts in confidence, authorship, and intention.

More than anything, it was a year marked by restraint. Local brands and creatives became increasingly deliberate about what they produce, how often, and why. In an industry long pressured by excess and constant output, this move towards intention felt radical.

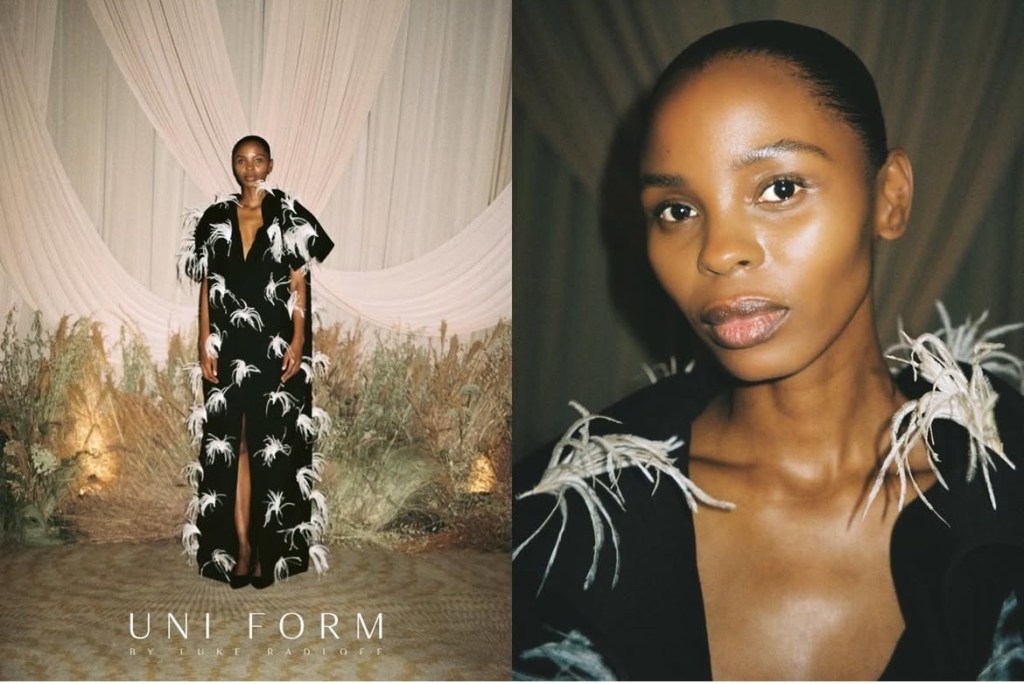

Uniform ZA, in collaboration with creative director Bee DIAMONDHEAD, embodied this shift with clarity. Their collection stood out not because it tried to dominate a season, but because it felt considered — rooted in African textile narratives, construction, and longevity. It reflected an understanding that clothing does not need to be disposable to be relevant.

This approach to sustainability moved beyond buzzwords. It echoed a cultural logic long familiar in African contexts: that garments carry memory, are worn with care, and often live many lives. To produce less, but with intention, became both an environmental and cultural act.

Designers like Lukhanyo Mdingi continued to contribute meaningfully to South African fashion through work that prioritises emotion, craft, and narrative. Even when output is measured, such contributions reinforce an important truth — that value in fashion does not lie in volume, but in depth.

It was a year less concerned with being understood and more committed to being honest.

At The Jozi Collective, we spent the year watching the culture. Not just the runways or press moments, but the spaces in between — the streets, studios, collaborations, and the everyday decisions creatives made about who they were speaking to and why.

A Shift Towards Self-Definition

One of the most noticeable changes was a growing refusal to over-explain. South African fashion — particularly from Black designers and youth-led movements — felt less invested in translation for external audiences. African references were not softened or framed as novelty; they existed plainly, confidently, and without apology.

This signalled a shift from seeking validation to asserting authorship. Designers increasingly created for communities that already understand the language, rather than for imagined global approval. In doing so, fashion became less performative and more truthful.

This confidence also extended to spirituality and symbolism. Thebe Magugu’s Sangoma-print–inspired dress stood out not because it shocked, but because it existed freely. African spirituality — long villainised, misunderstood, or erased — was presented without fear or justification. It reflected a growing comfort among designers to live fully within their references, rather than negotiating them.

Brands like Imprint ZA further reinforced this self-definition, continuing to build a contemporary South African visual language that feels lived-in, intuitive, and grounded — fashion that speaks softly, yet firmly, to its own context. This year, Imprint ZA also used fashion as a tool for social change. Their collection, created in support of the fight against gender-based violence, donated all proceeds to the Women for Change Organisation, which advocates for women’s rights across South Africa. This act of intentional creation underscores a growing trend: designers are not only shaping aesthetics but using their platforms to support communities, challenge injustice, and give fashion purpose beyond commerce.

Street Culture Set the Pace

Once again, the street proved more influential than any institutional calendar. Youth culture led not through polished statements, but through instinctive expression. Oversized silhouettes, layered identities, and deliberate “wrongness” appeared not as trends, but as attitudes.

This instinctive relationship with clothing was powerfully articulated through Waste Files: Afterlives of Fashion’s Excess in Johannesburg, a project by Khumo and Khanyi Masina, styled and creatively directed by Thato Nzimande, and featured for Dazed Middle East. Rather than framing waste as purely aesthetic, the project addressed a broader political reality.

In the past decade, it has become impossible to ignore the growing imbalance between scarcity for many and excess for some. The Global North’s attempts to manage overproduction have resulted in a new form of migration — not of people, but of waste. Colonial trade routes once used to extract resources are now repurposed to export discarded textiles back to the Global South, often to the very places where these materials originated.

Within this context, Johannesburg becomes both site and witness. Clothing is not discarded casually; it is reworked, repurposed, and worn again. Waste Files positioned street style not as trend commentary, but as historical response — a visual language shaped by survival, memory, and ingenuity. Thato Nzimande’s styling and creative direction brought this narrative into sharp focus, particularly in younger cultural spaces, demonstrating how street culture continues to lead with intelligence and care.

These looks were not trying to be archived or approved. They existed because they needed to. And in a country where fashion has long been entangled with survival, that kind of ease remains quietly radical.

Street style reminded us that relevance is not granted by platforms; it is earned through presence.

Fashion as Cultural Work

Throughout the year, it became increasingly clear that fashion in South Africa is doing more than selling clothes. It is documenting memory, negotiating identity, and recording how people move through a post-apartheid reality that remains unfinished.

Black-owned brands, independent stylists, photographers, and creatives are not merely participating in an industry — they are shaping a cultural archive. Their work captures how freedom is worn daily: sometimes loudly, sometimes gently, often without explanation.

This is fashion as cultural labour, not trend production.

Designers such as Rich Mnisi, Thebe Magugu, Imprint ZA, and others continue to build worlds through their work — worlds that hold softness, masculinity, intimacy, spirituality, and African futurity without compromise.

The People Holding the Culture

This year also reminded us that South African fashion is sustained by people whose work extends far beyond garments alone.

Figures like Nkhensani Mohlatlole continue to play a vital role in shaping fashion discourse through research, education, and documentation. By unpacking history and uncovering overlooked narratives, they provide context that allows the industry to understand itself more clearly.

Recognition took on a broader meaning with Wanda Lephoto receiving a Change Maker Award. Even without releasing a collection this year, Wanda’s ongoing commitment to reshaping perceptions, building platforms, and advocating for South African fashion remains deeply influential. Honouring such contributions reflects a growing maturity — one that values cultural impact alongside output.

Momentum was also visible in Onesimo’s fashion exhibitions, which found increasing resonance within art fair environments. Watching fashion exist in these spaces reaffirmed its role as voice — capable of critique, memory, and expression beyond commercial frameworks.

Visual storytelling remained central. Tatenda Chidora’s continued contribution to South African fashion, particularly through this year’s collaboration with Boyde, stood out for its emotional clarity and restraint. Together, they produced imagery that felt intimate, intentional, and deeply rooted in understanding rather than spectacle.

Collaboration remained essential. Tandekile Mkize continues to be one of the most impactful contributors within South African fashion — consistently pouring time, care, and vision into supporting designers and creative projects across the ecosystem.

Equally significant was the work of dickeranddane, whose photography captured a wide range of South African fashion brands and cultural moments throughout the year. From lookbooks to events like Confessions x Collections, their images contribute to a growing visual archive — one that documents South African fashion with sensitivity, pride, and precision.

Together, these individuals remind us that fashion culture is not sustained by designers alone. It is built by educators, image-makers, collaborators, curators, and thinkers — people who choose to show up, consistently, even when the work is unseen.

What Hasn’t Changed

Despite these shifts, certain realities remain. Access is still uneven. Visibility is still concentrated. Global recognition continues to be treated as the ultimate marker of success, even when local impact carries far greater weight.

These tensions are not failures of creativity. They are reflections of a broader system that South African fashion continues to navigate — and resist — at the same time.

Looking Ahead

As the year comes to a close, we are not interested in predictions or trend forecasts. What matters more is what we choose to pay attention to next.

At The Jozi Collective, we remain committed to the stories that exist between the runway and the street, between heritage and instinct, between visibility and meaning. We are interested in fashion as cultural expression, as documentation, as lived experience.

South African fashion is not perfect — but it is moving with intention. It is asking better questions, creating with care, and choosing honesty over excess.

If this year taught us anything, it is that South African fashion does not need to be louder to be powerful. It needs to be seen clearly, spoken about thoughtfully, and supported intentionally.

Leave a comment